By the time Reader-Response Theory emerges in the mid-twentieth century, the Enlightenment foundations of literary meaning have already been profoundly unsettled. Marxism has displaced meaning from individual consciousness to material and ideological structures; psychoanalysis has fractured the subject internally through the logic of the unconscious; postcolonial theory has exposed the universal human subject as a colonial fiction. In the wake of these critiques, neither authorial intention nor textual autonomy can convincingly guarantee meaning. Reader-Response Theory enters this intellectual landscape not as a restoration of subjectivity, but as an attempt to explain how meaning continues to occur after its traditional foundations have collapsed.

The central question it raises is deceptively simple: if texts do not contain meaning and authors do not control it, how does literature come to signify at all? The answer proposed is not that meaning resides freely in the reader, but that meaning is produced in the act of reading—an act shaped by psychological, structural, historical, and ideological forces. Reader-Response Theory thus relocates the crisis of subjectivity from the author or the psyche to the scene of interpretation itself.

The Reader After the Death of the Author

Reader-Response Theory must be understood as a response to the exhaustion of author-centered criticism. Once authorial intention is destabilized, the literary text can no longer be read as a closed system of meaning. Yet this does not lead to interpretive chaos. Instead, the reader becomes unavoidable—not as a sovereign subject, but as a mediating function through which texts are actualized.

Early reader-oriented theorists retain traces of Enlightenment humanism. Louise Rosenblatt’s transactional theory emphasizes the lived experience of reading. Meaning emerges through the interaction between reader and text, particularly in aesthetic reading, where emotional and imaginative engagement is foregrounded. While this approach successfully dislodges meaning from textual autonomy, it risks reinstalling a stable, experiential subject whose responses appear self-generated.

This limitation becomes clear when applied to a novel such as Pride and Prejudice. Readers’ sympathies toward Elizabeth Bennet vary historically and culturally. A purely experiential account cannot explain why certain readings become dominant at specific historical moments, while others fade. The reader’s response, far from being purely individual, is shaped by social norms, genre expectations, and ideological frameworks.

The Psychological Reader and the Persistence of Desire

A more complex model emerges in psychoanalytic reader-response criticism, particularly in the work of Norman Holland, who argues that readers interpret texts in ways that reproduce their own identity themes. Reading becomes a psychic event, structured by unconscious desire and defense mechanisms.

This approach resonates with Freud’s insight that meaning is never directly accessible but symbolically mediated. A text does not simply communicate content; it activates unconscious structures in the reader. Yet even here, the reader risks becoming an enclosed psychological unit. Desire is acknowledged, but its structural determination is underplayed.

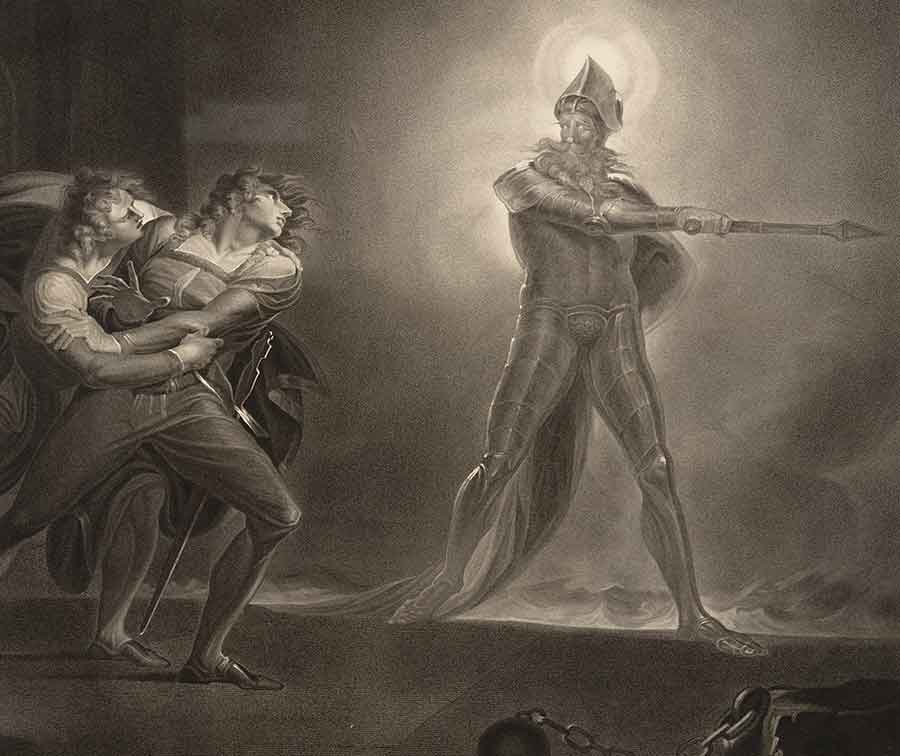

When reading Hamlet, for example, psychoanalytic criticism shows how readers may identify with Hamlet’s hesitation, guilt, or ambivalence. But the persistence of Hamlet’s interpretive instability across centuries suggests that something more than individual psychology is at work. The text itself is structured to resist closure, repeatedly frustrating the reader’s desire for resolution.

The Reader as a Structural Function: Indeterminacy and Gaps

The most decisive theoretical advance within Reader-Response Theory occurs when the reader is no longer treated as a psychological individual but as a textual function. In the work of Wolfgang Iser, literary texts are understood as fundamentally incomplete. They contain gaps, blanks, and indeterminate elements that require readerly participation.

Meaning arises through a structured process of anticipation and revision. The reader forms expectations, encounters disruptions, and reconstructs coherence. Importantly, this coherence is always provisional. The text never fully yields itself. Reading becomes a temporal experience, not a final decoding.

This model is particularly effective in interpreting modernist literature. In The Trial, the absence of causal explanation is not a flaw but a structural necessity. The reader’s repeated attempts to impose legal, moral, or psychological logic mirror Josef K.’s own futile search for meaning. The text generates interpretation by withholding resolution, transforming the reader’s frustration into a constitutive feature of meaning itself.

From a Lacanian perspective, these gaps function like lack. The reader’s desire to complete the text is continually deferred, producing interpretation as a repetitive act rather than a final achievement. Reading reenacts the divided structure of subjectivity itself.

Reader-Response Theory gains historical depth through the work of Hans Robert Jauss, who shifts attention from individual acts of reading to historically situated reading publics. Every text encounters a horizon of expectations shaped by genre conventions, aesthetic norms, and cultural assumptions. Meaning changes not because texts are unstable, but because readers are historically produced.

This insight aligns closely with postcolonial criticism. The reception of Heart of Darkness illustrates how interpretive horizons shift. Once read as a profound exploration of moral darkness, the novel is now frequently approached as a text complicit in colonial discourse. The text has not changed; the conditions of reading have.

Reception theory thus dismantles the Enlightenment belief in timeless literary value. Literary history becomes a history of interpretation, not of stable meanings.

Interpretive Communities and Ideology

The most radical articulation of Reader-Response Theory appears in the work of Stanley Fish, who argues that meaning is produced entirely within interpretive communities. Readers do not first read and then interpret; they interpret in order to read. What counts as evidence, coherence, or even textual presence is determined by communal norms.

This position reconnects Reader-Response Theory with Marxism and postcolonialism. Reading is not a neutral act; it is ideological. The reader is already positioned within institutional, cultural, and political frameworks that shape interpretation in advance.

A novel like Things Fall Apart illustrates this vividly. Colonial readers and postcolonial readers do not merely disagree about the novel’s meaning; they inhabit different interpretive communities with different assumptions about culture, history, and narrative authority. Meaning emerges not from the text alone, but from the social location of its readers.

Reading as the Final Site of the Crisis of Subjectivity

Seen within the broader arc of modern literary theory, Reader-Response Theory does not resolve the crisis of meaning—it completes it. The reader, like the subject of psychoanalysis and the citizen of Marxist critique, is divided, structured, and historically produced. There is no free reader, no innocent interpretation, no final meaning.

Reading becomes a scene where desire seeks fulfillment and encounters deferral, where ideology organizes perception, and where history silently governs response. Literature does not offer mastery; it stages the impossibility of mastery. Each reading is an attempt at closure that inevitably remains incomplete.

In this sense, Reader-Response Theory does not mark a return to the subject but its final displacement. Meaning survives not as essence or intention, but as an event—fragile, contingent, and endlessly renegotiated. The Enlightenment dream of transparent understanding dissolves once more, this time at the very moment of reading itself.